Winter 2024 Newsletter

Dear Friends of the Michigan League,

Graciously allow me to start by thanking you for being part of our community. Simply put, we could not do what we do without each of you. And while I know our connection spans time and space, be assured your friends at the Michigan League think of you, our beloved community, often.

As I write to you from the Michigan League, the spirit of celebration and rejuvenation fills our spaces at the Michigan League. This new season is a reminder of the amazing accomplishments that have taken place thus far in the academic year, and a beacon for what’s ahead in 2024. I’m grateful for the Go Blue community that helps spark meaningful memories, new connections, and personal/professional growth.

I’d love to share with you some of the meaningful moments that have transpired at the Michigan League and to introduce you to a few of the talented students behind the scenes.

Warm Regards,

Xavier A. Wilson

Director of the Michigan League

Associate Director of University Unions

Spotlight on Michigan League Student Employees and Young Alumni

With the fall term moving into the final sprint toward winter break, the Michigan League reflected on how refreshingly familiar this current campus rhythm feels.

Throughout every term, what hasn’t changed is our dedicated student employees working alongside our permanent staff. Our group of recent alumni is also unique. They navigated the return-to-campus experience both as students and as League employees, often tasked with helping others wayfind within our space.

We spoke to four of our past employees about what the League meant to them, from their favorite parts of their job to what they learned about themselves while working in our beautiful, historic gathering space.

In these conversations, a clear and common thread emerged: connections and community. Each expressed the importance of these two human needs and their observations of how their work at the League facilitated both. Sometimes these themes were expressed definitively; other times, the sentiment was shared in more muted terms.

Yet the conclusion is straightforward: These students share our love for not only the League’s physical form, but for the place it holds in our hearts.

We’re delighted to introduce you to those students and share their stories.

Meet Maddy Mayer

Maddy Mayer is familiar with the mix of emotions—and questions—that may accompany being the first to do something.

That’s why the recent U-M alumna (BA, ’23) loved meeting high school seniors and their families and supporters while she worked as a Campus Information student manager.

“As a first-generation student, I can often relate to a lot of these families and can connect them with the programs and resources that will best serve them,” Mayer said. “It always feels really fulfilling to see the students’ faces light up when I mention something that they may not have heard about otherwise.”

While sparking excitement about U-M among prospective students, Mayer, who earned a dual degree in psychology and elementary education, said the League has built their own confidence and patience, two skills that will be invaluable in their future teaching career.

“While working the desk, working with other students or working with full-time staff members, it can be extremely important to be confident in your own knowledge and abilities,” Mayer said.

As a student, Mayer shared how they would “often run into situations where I am not taken seriously. By growing my own confidence through this job, I have opened many more doors and opportunities for myself.”

Beyond the on-the-job skills Mayer developed, the League supported their professional development in another way in 2021: Mayer was named a recipient of the Mary F. Kinley Scholarship Fund. Named in honor of long-time League supporter and board member Mary Kinley, the scholarship provides League student employees with educational opportunities.

Meet Benjamin Davis

“Tell me about yourself.”

It’s the type of question Benjamin Davis often asks his fellow student co-workers, driven by a deep curiosity and desire to meet and learn from the people from all over the world who walk into the League.

“It’s the anthropologist in me. I can’t help it,” said Davis, who earned degrees in anthropology and linguistics in 2023, with minors in digital studies and museum studies. Most recently, Davis served as building manager at the League and the chair of the Board of Governors.

Joining the Michigan League’s Operations department in the fall of 2019 as a set-up staff member, Davis credits his experience working in the League for “pushing my boundaries and forcing me to grow in my character.” From Davis’s co-workers who made “every time I clock in a great experience” to the chance to interact with the distinguished speakers the League welcomes each year, the sources of inspiration are limitless.

Davis grew up in Ortonville, Mich., a small town located about an hour’s ride north of Ann Arbor. Growing up in a rural region, Davis’s exposure to other cultures was limited.

“Coming to campus and working at the Michigan League has allowed me to meet so many interesting and inspiring people,” said Davis.

Davis’s love and historical knowledge of the League runs deep.

Citing the League’s foundations as a haven for women on campus to seek community and camaraderie, Davis shared what he loves most about the Michigan League: its history of supporting women and voices on campus that are not heard.

“The fact that the League still has a commitment to supporting women and other marginalized groups fills me with pride,” Davis said. “I am honored that I am able to be a part of a building that stands against political and social oppression, has a legacy of inclusion, and that still today supports diversity, equity, and inclusion wherever it can.”

As a recent U-M graduate, Davis’s contributions as a former student employee are now interwoven with the Michigan League’s rich historical foundation.

“My experience serving as the Chair of the Board of Governors was the cherry on top of my time at the Michigan League,” said Davis. “Being able to serve the building and be a voice for students within the building and University Unions as a whole was truly an honor.”

Meet Penny Petersen

When Penny Petersen was not helping prospective students and their families get settled at the Inn at the Michigan League, the recent U-M graduate and former student manager became an explorer.

“I enjoy the architecture of the League,” Peterson said. “It’s such a fascinating and beautiful building, with lots of nooks and crannies filled with lovely surprises.”

Among her favorite discoveries: the League technically has a fifth floor, which is where the permanent housekeepers used to live.

Beyond Petersen’s physical and factual finds, Petersen shared how her roles at the Inn—first as a concierge beginning in August 2022, and later as the student manager—provided her an opportunity to discover and strengthen skills such as communications and problem-solving capabilities.

“The opportunities I’ve had at the League have helped me to improve my leadership skills,” Petersen said. “I have learned to be more patient, become a better teacher, and developed a better sense of compassion for my coworkers. I’ve learned to be concise yet friendly over phone and email, and to remain calm and confident while navigating through small issues that arise.”

One part of her role she will miss most is interacting with future Wolverines and their families.

“It’s always fun to hear where they’re coming from and what they hope to study, and to be able to offer information including my own experience as a student,” Petersen said.

Meet Abby Dornoff

Customers at Maizie’s Kitchen and Market at the Michigan League can taste the difference Abigail “Abby” Dornoff made while working with Maizie’s culinary team.

This fall, Maizie’s debuted a new lineup of menu entrees and sides influenced by Dornoff, who focused on nutritional sciences as a graduate student in the U-M School of Public Health. The three-week rotating lineup is displayed on another Dorhoff contribution: a new electronic template for menu planning.

At Maizie’s, Dornoff (MPH ’23) found a space where mixing her passion for the food industry with knowledge from the classroom formed a winning recipe: a positive impact on customers and staff alike.

In the fall of 2022, Dornoff transitioned to Maizie’s from a different Michigan Dining unit—and the timing proved to be a perfect combination. Maizie’s management and culinary teams had started a project to reimagine Maizie’s menu, which debuted in Fall 2023. Dornoff noticed the visual menu board remained mostly untouched for weeks, and approached Maizie’s Manager Chris Tanner with an idea.

“This is my entire degree. Can I please help with this?” Dornoff recalled sharing. “This is my niche!”

Tanner met Dornhoff’s request to lead Maizie’s new menu development project with a resounding yes.

“Abby was known for always asking questions,” said Maizie’s Manager Chris Tanner. “Lots of whys and what ifs. It was enjoyable answering her questions because you knew they were going somewhere and had lots of thought behind them.”

“She pushed others to get their views and insights and, of course, was always ready with another challenging question,” said Tanner.

From that moment, Dornoff combined her knowledge, passion, and creativity to help Maizie’s solve what she described as a puzzle. Maizie’s management and culinary staff teamed up with Dornoff to set project goals and brainstorm ideas for crafting a menu that could both attract new customers and satisfy current customers’ taste buds.

What Dornoff first thought “would be easy” soon required a broader view as the team considered which factors appealed to various audiences, from those dining at Maizie’s to the staff cooking and serving customers.

In the classroom, “ making these [menu] changes are easy,” said Dornoff. “I quickly learned the process of how a new menu item is developed is extensive.”

Sustainability featured heavily in reinventing Maizie’s menu. Dornoff applied sustainability goals throughout the creative thinking process. Her inquisitive nature led Dornoff to ask how Maizie’s could diversify its protein offerings and help customers consider new options beyond their usual selections.

Originally from Colorado, Dornoff returned to Fort Collins, Colo., after graduation to work with a local restaurant, pursuing opportunities to work on quality assurance as a food safety manager.

“Abby definitely made a difference working as a student manager working side by side with management and her student peers,” Tanner said.

Taste an Abby-influenced fall lineup of entrees and sides at Maizie’s during your next trip to campus!

Visit Maizie’s to taste the new lineup of entrees and sides influenced by our very own 2023 public health alumna!

In focus

League Ballroom audio, visual system receives upgrade

Visitors who step inside the Michigan League Ballroom for the first time since the pandemic may believe their eyes and ears are deceiving them. But rest assured that the space’s improved sound and image quality are no illusion.

A scheduled-but-pandemic-paused audio and visual (AV) system upgrade was recently completed after a two-year hiatus during COVID-19, after nearly two years of project planning.

The results were worth the wait.

The sleek new AV system replaces the previous projector and sound system, while adding new features that help make every seat, regardless of the room setup, one of the best spots in the space. A second mounted projector and new, automatic screens gives event organizers greater flexibility in where and what images they share.

Other upgrades include new audio speakers and control panels, updated programmable controls, a refurbished lectern and new wireless microphone system.

A magnet for event planners and campus colleagues seeking a spacious and elegant space, the Michigan League Ballroom upgrades were vital to one of the central campus’s larger meeting and event spaces. The ballroom can accommodate between 350 to 500 people, depending on whether the room configuration is banquet or auditorium style.

Now, wedding ceremonies and receptions, university seminars and conferences, research symposiums and student organization events will have access to state-of-the-art equipment at their next event in the Michigan League Ballroom.

A familiar face

Something felt, no, looked, different. Sheryl Szady knew it—and she was staring at the physical proof.

It was January 2018. Szady, a three-time University of Michigan alumna, was at a meeting of the U-M Kinesiology Alumni Society’s Board of Governors. She had not taken more than a few steps inside the conference room when she spotted it: an unassuming, partially crumbling female bust.

It was the answer to a question Szady, who is also a member of the Michigan League Board of Governors, had begun asking nearly three years earlier: Where is Alice?

In 2015, Szady discovered a bust of Alice Elvira Freeman Palmer—a, as one historian called her, dominant voice in the then-burgeoning arena of women’s higher education in the late 1800s—was gifted to U-M. Szady believed it to be lost forever as the details of its Ann Arbor arrival faded with the passage of time and a short paper trail. Fast forward to 2018, when mid-meeting, Szady realized that she had stumbled upon Alice’s bust in the School of Kinesiology, tucked away in the fourth-floor conference room in the Observatory Lodge Building.

Szady’s search for the lost and long-forgotten bust ended in that room, while her quest for answers and efforts to bring Alice home to the Michigan League were beginning once more.

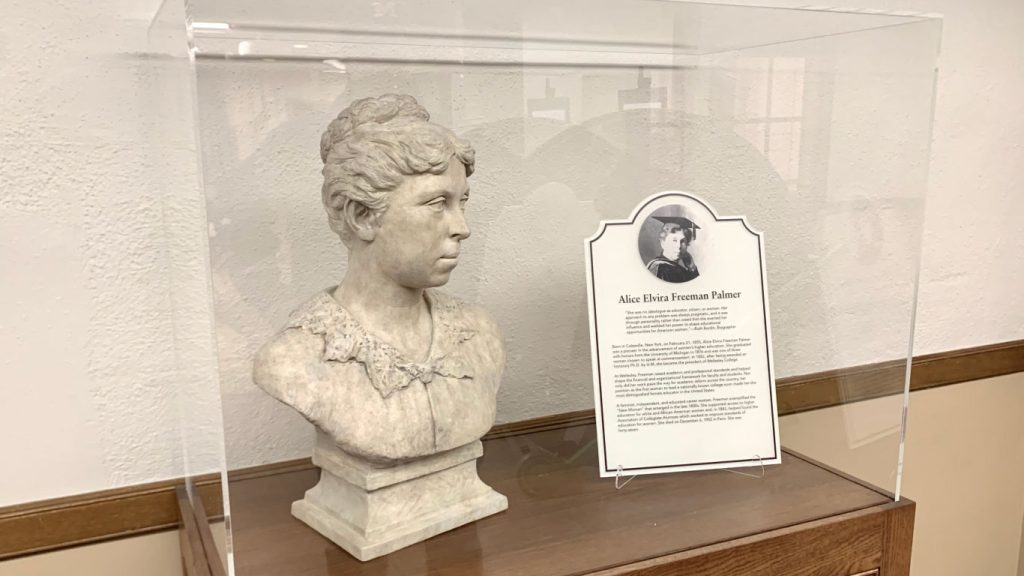

Today, the Freeman Palmer bust is prominently displayed on the League’s third floor, encased in glass for new generations to learn and celebrate her advocacy in women’s education and connection to the League. But the bust’s journey is a curious tale, one with scenes seemingly torn from the pages of a classic whodunit.

A strong presence, preserved in stone

In 1870, U-M made history when it became one of the first universities in the United States to admit women, what many men at the time called a “dangerous experiment.”

Women were undeterred.

Among those first cohorts of women at U-M was Alice Elvira Freeman, who grew up on her parents’ small farm in New York with aspirations of attending U-M rather than a women’s college. Her U-M journey almost ended before it began, as then-University President James B. Angell decided to conditionally admit Freeman despite her underperforming on the entrance exam. Angell’s decision helped launch Freeman’s educational barrier-breaking academic career and he remained a close confidant and professional ally, though the path she carved was one whittled from her own tenacity in defiance of the status quo.

Freeman graduated with honors from U-M in 1876, one of three women chosen as commencement speakers for the Class of 1876. She went on to a distinguished academic career that included becoming the chair of Wellesley College’s history department in 1879 and named president of the college two years later. Her presidency cemented Freeman’s place in the history books, as she became the first woman to lead an independent, nationally known college in the nineteenth century. At the time, it catapulted her to a revered role as the most distinguished female educator in the United States. In recognition of her achievements, and at the age of only 27 in 1882, U-M awarded her an honorary degree of Doctor of Philosophy.

She later became a key figure in the Massachusetts Board of Education and the first Dean of Women at the then-newly founded University of Chicago before her death in 1902 at the age of 47.

Even as her own academic stature rose, Freeman worked to ensure that the women who followed had a clearer path to pursuing knowledge. In 1882, she co-founded and later served as president of the national Association of Collegiate Alumnae, which united college-educated women to increase educational opportunities for women and later became the American Association of University Women (AAUW).

George H. Palmer, Freeman Palmer’s husband and a professor at Harvard University, commissioned several art pieces—busts and paintings of Alice—to commemorate her campus contributions at several higher education institutions, including U-M.

U-M’s gifted piece made it to Ann Arbor; of this much Szady was certain.

A July 1924 letter that U-M President M.L. Burton sent to George both clued in Szady to the bust’s existence and confirmed its delivery. In the handwritten letter, Burton informed George Palmer that the “the beautiful bust of Mrs. Palmer” was moving from his home library to its temporary home in the “office of the Dean of Women in Barbour Gymnasium, which is the center of the student life of the women.” From there, Burton assured George that “just as soon as our Michigan League Building is constructed it will be given a place of honor in that building.”

In 1928, four years after the letter’s postmark, the cornerstone for the Michigan League was laid. One year later, the League opened to the public, almost certainly without the Freeman Palmer bust.

It would take nearly a century—and one woman’s never-forgotten investigation—for Alice to make her way home.

Lost, then found

It was February 2015. Szady was researching the Alice Freeman Palmer Professorship Fund, part of a broader review of endowment funds she was conducting for the U-M College of Literature, Science, and the Arts.

The contents of Burton’s note had caught her eye. Szady’s involvement with the Michigan League spanned decades, yet Burton’s letter marked the first time she had heard of a bust for Freeman Palmer, an icon in women’s higher education, destined for the League.

That left Szady with an unanswered question: Where is Alice?

As a member of the Michigan League Board of Governors, Szady made it her mission to locate Alice and bring her bust to its intended home within the League. She turned to her wide circle of U-M colleagues and contacts for help. The Michigan League director. Her Friends of the League colleague who handled art acquisition. The U-M Office of the President. The Bentley Historical Library. The U-M Museum of Art. A university committee that oversaw a database of art on campus. The Michigan Union.

No one knew where it might be; many did not know the bust even existed before Szady’s inquiry. The trail went cold as Szady exhausted her options. Life moved on. So did Szady. That is, until the School of Kinesiology’s planned move into the renovated School of Kinesiology Building helped crack Szady’s cold case.

“It was lost, broken, who knows,” Szady said. “All I knew was that it had disappeared from the landscape.”

In January 2018, three years after Szady first learned about the Freeman Palmer bust, she was startled by an unexpected and unfamiliar face in the Observatory Lodge Building.

At the other end of the room—the same room she had walked into for years to attend Kinesiology Alumni Society’s Board of Governors meetings—a woman’s bust was now perched atop a bookshelf. Huh?

“When you’re a historian of sorts and you find leads, you have to act on them immediately,” Szady explained of her initial days-long fact-finding process in 2015. “Otherwise, you forget them until someone mentions something.”

Or until the evidence is staring you in the face.

“I walked into the conference room, which I have walked into for years, and now there’s a bust that hasn’t been in the room before,” Szady recalled. “I asked the alumni society staff ‘Who’s that?’ They had no idea. I asked where it came from. They said, ‘You know, I think Professor [Katarina] Borer is retiring. We’re cleaning out her office.’”

Aha.

Around her, the U-M School of Kinesiology Alumni Society meeting was underway, but Szady had other business. She took her sleuthing to Google, searching for photos connected to a name that she occasionally thought of in her idle moments: Alice Freeman Palmer.

“At this point, I knew there was a bust, but I had no idea if it still existed. But now I see this bust appear in Kinesiology. Everyone in this meeting is listening to the chair, except me. I’m highly distracted,” said Szady with a chuckle.

She found a photo of Freeman Palmer in the same pose as the female bust. Triumphantly, she held up her phone. “Here she is. This is Alice Freeman Palmer,” Szady recalled announcing to her fellow kinesiology alumni board members.

Confused, the group asked, “Who is that?”

“She was a student at Michigan and a great champion of women in higher education,” Szady responded.

“That’s nice. What is she doing here?”

Szady found Alice. Now with one mystery solved, another unfolded.

Connective tissue

Szady knew Borer, now professor emerita of Movement Science. Szady also happens to hold an almost encyclopedic knowledge of faculty within the U-M School of Kinesiology, from which Borer retired in May 2018 after spending more than 40 years at U-M.

This cerebral connection may be built on Szady’s own prominent place in advancing the position of women at U-M. When Szady arrived as an undergraduate student at U-M in 1970—seven years before Borer joined the faculty as an assistant professor—there were no women varsity sports.

Szady joined the field hockey, volleyball and basketball club sports, but her competitive streak pushed her into a leading role in the fight for equality on the athletic field. With the passage of Title IX in 1972, Szady led efforts to create six women varsity teams, becoming captain of the first varsity field hockey team in 1973 and playing on the first varsity basketball team in 1974.

Szady’s personal push for athletic equity and her time as a student in the U-M Department of Physical Education—which separated from the School of Education in 1984, became the Division of Kinesiology in 1990, then the School of Kinesiology in 2008—left her well versed in the history of sex-based separation that persisted across campus long after U-M’s first women enrolled and graduated.

There is no immediately distinguishable link between Alice Freeman Palmer and the women-only Barbour Gymnasium, the location that U-M President Burton said would serve as the temporary home of Alice’s bust until the League’s opening. Yet the spaces in which the Freeman Palmer bust most likely sat for decades reveal a connection, even if a serendipitous one. For more than 90 years, the bust of Alice Freeman Palmer, unknown to passersby, sat in the shadows of strong women fighting for equality in all facets of higher education.

Beginning in 1894, the recently completed and men-only Waterman Gymnasium began holding women-only hours each morning. The change was in response to a call from the Association of Collegiate Alumnae—the national organization that Freeman Palmer co-founded in 1882—that U-M provide physical activity options for women.

The gym also served as a meeting space for the Women’s League, a small group of college women that formed in 1890. Here, the group launched a capital campaign. The goal: to build a gymnasium for women that would be a part of the Waterman Gymnasium building. With nearly all the campus’ women’s organizations focused on this shared goal, the effort raised nearly $21,000, with the U-M Board of Regents contributing the approximately remaining $20,000. The space opened in 1897 and two years later, the Regents voted at its January 1898 meeting to name the building for former Regent Levi L. Barbour, acknowledging that the Regents’ portion of the financing stemmed from the sale of land in Detroit that Barbour gave to U-M.

The more than 35,000-square-foot Barbour Gymnasium’s first floor rooms served as parlors and offices for the Dean of Women and the Department of Physical Education for Women, and as a social space for U-M women students.

In 1948, half a century after the addition of the Barbour Gymnasium led to the formation of the Barbour and Waterman Gymnasium complex, the offices of the Dean of Women vacated the space, leaving the gym entirely to women’s physical education.

The men’s and women’s physical education programs merged beginning in 1970. In 1977, the complex’s fate was sealed and the gyms were demolished to provide room for an expansion to the adjacent Chemistry Building. U-M’s Physical Education faculty, losing their home in the Barbour and Waterman Gymnasium complex, resettled in the newly built Central Campus Recreation Building (CCRB). By fall 2007, Kinesiology transitioned to the historic Observatory Lodge Buildng on central campus, which housed some of its administrative offices.

Szady has a working theory: Alice was there for every move physical education, which later became Kinesiology, made across campus. All until 2021.

Alice’s journey home

Kinesiology staff memories may disprove some part of that theory. Or at least offers an alternative path for Alice’s journey to the League.

Before Ruth Harris, professor emerita of kinesiology, moved to the CCRB, Szady recalled that Harris’s office sat in the back of the Barbour and Waterman gym complex.

“It almost looked like a sunroom,” Szady said. “I don’t remember seeing the bust in there, but my guess is she took hold of it so it would not be lost.”

It’s a plausible scenario, if the Freeman Palmer bust spent more time in the Barbour and Waterman gym complex than planned, which is what Szady suspects.

In Burton’s 1924 letter to Alice’s husband, he indicates that the bust was headed to the “office of the Dean of Women in Barbour Gymnasium.” When the Dean of Women offices left the gymnasium complex in 1948, Szady guessed that while important papers and other lightweight items made the move, heavier items like the Freeman Palmer bust were likely left behind.

Decades remain uncounted for Alice’s whereabouts.

The bust’s movements between 1924 to whatever year Harris may have brought the bust to her office remains unknown. Szady recalled that Katarina Borer, professor emerita of Movement Science, moved into the late Harris’s office, then located in the CCRB, and likely inherited the Freeman Palmer bust.

Borer’s office remained in CCRB, and the bust sat on her window ledge, until her retirement in 2018. No one is quite sure how the bust made its way to Observatory Lodge’s fourth-floor conference room, where Szady spotted Alice during the U-M Kinesiology Alumni Society’s Board of Governors meeting.

After Szady secured support from the Michigan League Board of Governors to bring Alice home and the School of Kinesiology transferred ownership of the bust to the Michigan League, one more unexpected twist almost derailed Alice’s long-awaited League arrival.

In December 2020, Szady received an email from Kinesiology’s associate director of development. The school’s offices were moving to their new building and Szady needed to come get Alice. Now. On a chilly Michigan winter day, Szady hopped into her car, headed to Observatory Lodge and a staff member slid the bust into Szady’s back seat.

And soon, Szady began receiving calls from an unknown number.

One day, she answered.

“‘I understand you have the bust of Alice,’” Szady said she recalled hearing. “She identified herself as with the Ann Arbor branch of the American Association of University Women.”

The same organization that can trace its roots back to the national Association of Collegiate Alumnae, which Freeman Palmer co-founded.

The Ann Arbor branch learned of Alice’s whereabouts thanks to member Marie Panchuk, who also sits on the Friends of the Michigan League board with Szady.

The branch, the mysterious voice told Szady, wanted to support efforts to restore and display Alice inside the League.

Another woman, Meg Brown, would be in touch soon, the voice shared.

After another call, Szady had a date and location to drop off Alice. And in yet another plot twist, Szady later remembered her own connection to the Browns.

Decades earlier, Szady once stood in front of the U-M Board of Regents advocating for varsity women’s sports. Among those Regents was Paul W. Brown, Sr., Meg Brown’s husband. The duo are the parents of current U-M Regent Paul W. Brown.

Years later, Szady and Regent Emeritus Brown would reconnect. One day, after repeatedly seeing one another at a local restaurant, the two exchanged pleasantries. And realized their paths previously crossed, albeit briefly. A friendship formed.

And now, Alice had brought the Browns and Szady back together.

As Meg Brown neared the end of her term as the Ann Arbor AAUW branch historian, she received an email from the current branch president, Mary Mostaghim.

Mary’s message: I need you to look into this.

Another Ann Arbor AAUW member, Marie Panchuk, had a lead on the whereabouts of an Alice Palmer bust in need of repair and a proper place of recognition. Marie also happened to serve on the Friends of the League board alongside Szady.

Aha.

Meg Brown was connecting her own dots, discovering that her friend Szady had the bust and asking Szady to bring the sculpture to ther home. Soon, Alice was in Brown’s back seat headed to Detroit.

Alice’s next stop: the Detroit-based Conservation and Museum Services.

Meg Brown knew an excellent and experienced restorationist who did work for U-M, the Detroit Institute of Arts, and many museums of history. The perfect place, Meg decided, to assess Alice’s condition.

Eventually, the Browns brought a restored bust, and unpaid bill for restoration services, back to Ann Arbor. Conservation and Museum Services remained patient with payment and recognized the project’s sponsors were, mainly, volunteer groups with minimal funds.

Soon enough, dots would connect once more and bills paid, thanks to generous financial support from the U-M Alumni Association.

The Browns were welcoming their son-in-law and U-M alumnus, Bob Stefanski (MSE ’86, JD ’89), for a visit at the same time the bust returned to their home.

Stefanski was in Ann Arbor to attend an U-M Alumni Association board meeting, and became another key link in Alice’s journey.

Within a short time, the U-M Alumni Association Board gifted the full restoration cost to the League’s Foundation.

The Ann Arbor branch of the AAUW paid for the plaque that now sits alongside the bust, erasing Alice’s past anonymity.

With all the puzzle pieces falling into place—and Alice no longer sporting chipped pieces—the bust was added to the League’s third floor.

A celebratory reunion

On a sunny November afternoon in 2023, many of the same individuals who helped throughout Alice’s journey reunited in a room on the League’s third floor.

There was Szady in the front of the room, sharing a condensed story of her sleuthing.

“It’s an honor to be here to recognize Alice Freeman Palmer, our patron saint of higher education,” Szady told the crowd of about 40 people.

“Yes!” echoed around the room. The affirmation came from several leaders and members of the Ann Arbor branch of the AAUW sitting in the audience.

There was Meg Brown, without whom the bust may have remained in disrepair, perhaps tucked away and out of the public eye.

Sitting in the crowd was also both Paul Browns. Members of the Michigan League Board of Governors. Friends of the Michigan League.

The group had gathered for a dedication ceremony in honor of the Alice Freeman Palmer bust.

A celebration years in the making.

The group radiated warmth and joy. The type of warmth that is the heart and spirit of the Michigan League.

“I’m very happy to be part of recognizing the wonderful aspect that U-M is home to great leaders for women’s higher education. It is great to see U-M history come alive,” Szady said, reflecting on a yearslong journey.

Alice now sits in her final resting place at U-M—until the next renovation puts her on the move again.

Inspired by Alice’s journey home to the Michigan League? Your gift to the Michigan League Annual Fund helps support art restoration efforts and other projects that keep our space a hub of student involvement.

A hidden gem

Emily Wilkins’s family shares a decades-long connection with the Michigan League. That’s why the U-M undergraduate student shared their surprise at first discovering the Inn at the Michigan League in 2022.

Wilkins talks with Michigan League Director Xavier Wilson about sustainability efforts at the Inn.